I swear I have had multiple posts eaten by websites in the past month. I had a whole bunch of Tweets scheduled and they disappeared and I had this post queued and it disappeared. I’m already so busy and scattered, websites losing my queued posts is literally the last thing I need. Anyway, a few weeks belatedly, here’s the quarterly Spring post. *shakes fist at the rapidly enshitifying internet*

Anyway, I survived my first semester teaching and I have a summer of reading ahead of me. This spring was defined by half finished books and reading fewer articles than I would have liked as I tried to find a balance of grading and class prep and my own homework. For the summer, I’m on a ticking clock to read a lot of books and begin assembling my thesis reading list, meaning that the Summer 2024 post is going to be unhinged in its own special way.

Finished:

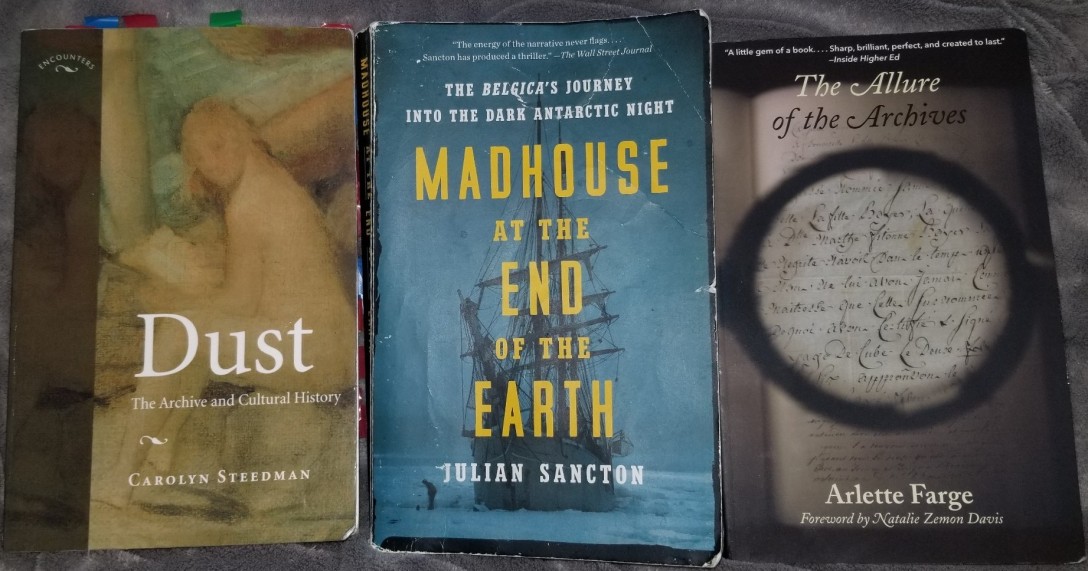

Madhouse at the End of the Earth by Julian Sancton – This was actually a reread, but I’d forgotten most of the audiobook and I was reading it with new intent. I picked it up as a possible thesis book because of how Sancton explores the public rhetorics that surrounded the Belgian Antarctic Expedition—from de Gerlache’s obsession with how the Belgian press and public at large would perceive his decisions/failures/successes, to Cook and Amundsen’s intentional construction and manipulation of their personal and public narratives as explorers in the public eye: see Cook’s falsehoods regarding the successes of his later expeditions and Amundsen’s self fashioning as a polar hero.

“Of Historicity, Rhetoric: The Archive as Scene of Invention” by Barbara A. Biesecker – This short article presents archives as sites of historical invention. No discovery, recover, etc. invention. Pointing to there being no “fixed” historical record, only what we create from what remains. She explores this through the controversy surrounding two museum exhibits about the Enola Gay and what they claimed as history through what they did and didn’t include. It’s a fascinating read, and only about 7 pages.

“The History of European Archives and the Development of the Archival Profession in Europe” by Michel Duchein – This is one of those articles that I could see a lot of the people outside of the field calling boring, but I loved it. It’s a quick, effective breakdown of how modern archival science isn’t the product of a single “European model,” since the archival “models” in Europe are actually extremely varied in their developments and practices. It also ends before the digital archive boom, being an article from 1992.

“Rethinking Access to the Past: History and Archives in the Digital Age” by Thomas Peace and Gillian Allen – This article asks us to consider how we can recover and make accessible scattered archival collections of marginalized communities through digital collections. Peace and Allen here are specifically speaking to Mi’kmaq people in Acadia, and how archival materials, and making them accessibility through digitization, can help not only recover, but showcase community history.

In Progress:

Dust: The Archive and Cultural History by Carolyn Steedman – I’m about halfway through this book and I adore it, it’s technically a collection of essay, but they flow together in a way that you wouldn’t know if they weren’t included like that. Steedman takes apart and complicates the theory that Derrida presents in Archive Fever, so if you struggle to read Derrida (like just about anyone), I would highly recommend Dust to supplement that.

The Allure of the Archive by Arlette Farge – Like Dust, this books presents a theory of working in the archives that goes beyond the basics of examining the items in the archive and speaks to the experience of working in an archive. Unlike Dust, Allure does it through the narrative experiences of the author as she does her work in the archive. It’s a more story-centered approach, as opposed to Dust’s heavy theory approach. They’re both excellent, and I’ve loved reading them in tandem.

If you enjoy my articles, please consider buying be a Kofi or supporting me on Patreon.